Since the financial crisis in 2008 a desperate cry has been

made by many economic and public policy experts: Bring back the Glass-Steagall

Act! The demand has graced the pages of hallowed financial publications like

the Wall

Street Journal and Forbes. Groups of average Americans have formed Facebook

groups to push the Act’s revival. It was name checked in the arguably

amorphous list of demands by Occupy Wall Street movement of two years ago. Multiple

Nobel Prize Winning Economists have lamented its repeal.

So, a lot of people were likely delighted by the recent news

that two unlikely allies, Senator John McCain (R-AZ) and Senator Elizabeth

Warren (D-MA) have mounted an attempt to

bring back many of the features of Glass-Steagall. These same people will also be equally disappointed

when the bill is slaughtered before it even gets a vote.

Why am I so confident (or cynical might be the right word)

that the bill won’t see the light of day? For a couple of reasons really, but let’s

first back up and look at what Glass-Steagall was.

Following the Stock Market Crash of 1929 and the ensuing

economic devastation, Congress pulled together and passed the Banking Act of 1933.

This bill established the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) and set

new regulations on speculation and banking. Included in the bill were

provisions set forth by Senator Carter Glass (D-VA) and Henry Steagall (D-AL)

that created a hard wall between depository and investment banks—that is, under

this provision a low-risk commercial bank that took customer deposits, issued

receipts and lent money would not be able to make the high risk financial

maneuvers that banks specializing in securities and investments could. This was

to avoid the potential loss of said deposits in failed investment strategies

since those deposits were never explicitly made by customers for the purpose of

speculation.

Blocking the unnecessary exposure of commercial deposits to

the wild valuation swings of speculative investment activities should be common

sense considering the aforementioned FDIC program and its responsibility to

insure commercial bank deposits. As Nobel Prize Winner in Economic Sciences

Joseph Stiglitz pointed

out in 2009:

“Commercial banks

are not supposed to be high-risk ventures; they are supposed to manage other

people’s money very conservatively. It is with this understanding that the

government agrees to pick up the tab should they fail. Investment banks, on the

other hand, have traditionally managed rich people’s money—people who can take

bigger risks in order to get bigger returns.”

But common sense and profitability don’t always overlap and

the financial industry tends to be more interested in the latter. They weren’t

concerned about the FDIC being on the hook if things went sour. They simply wanted

the ability to merge investment and depository banks to tap into those

commercial balance sheets for further investment leverage.

And more often than not, it seems, what the financial

industry wants the financial industry gets. So, in late 1999 lobbying

expenditures of roughly $300 million and years of working the back channels of

Washington culminated in the financial industry getting what it wanted: a silver

bullet bill—the Gramm Leach Bliley Act— that definitively erased Glass Steagall

from the regulatory tool kit. Immediately, mergers between commercial and

investment banks began en masse.

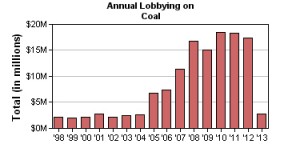

So, the first reason that the McCain-Warren effort to bring

about a return of Glass-Steagall-styled banking regulation is largely an

exercise in futility is that the financial industry simply doesn’t want it to

happen. And they spread enough money around Capitol Hill and K-Street to be

heard loud and clear. Just last year’s combined Commercial and Financial

Banking lobbying expenditures totaled over $159 million which put it third

highest on the list of total industry lobbying expenditures. That’s an

undoubtedly hefty investment, but it has paid off time and time again. It

worked to repeal numerous banking regulations throughout the 80’s and 90’s, it worked

to finally kill Glass-Steagall in ’99 and it’s working again as the industry

has largely been successful in emasculating the Dodd-Frank Act; the first

attempt at wrangling in the excesses of Wall Street following the 2008

financial implosion. Let’s take a closer look at how the financial industry

reacts to legislation that it doesn’t care for:

Following passage of Dodd Frank in 2010—no small miracle in

itself, even with the American people considerably outraged at that point—the

financial industry went into overdrive on the Hill. Their strategy was a

multi-pronged approach. First, they sent in a veritable army of lobbyist to

persuade Congress members to defund the regulatory agencies necessary for

enforcement of the bill. In a long, fairly underreported fight, bank lobbyists outnumbered

the bill’s advocates 20

to 1. They outspent the bill’s advocates by an even larger margin. They

also got more face time with representatives by a margin of nearly 9 to 1. This

fire-hose approach proved rather effective. In addition to cutting off

significant funding, they also successfully pushed to have all of the rules and

legal language of the bill written by the individual regulatory agencies

themselves.

The second part of the assault was a wave of regulatory

attorneys. If a regulator were to somehow successfully publish a rule, the

banks would immediately take that regulator to court and, at the very least,

effectively gum up the rule’s implementation for years; sometimes only over

minor technicalities. One such litigator, Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia’s

son Eugene has already filed seven of these types of suits. Long story short:

Less than half of the rules that had been outlined in Dodd-Frank have been

finalized. It’s basically a zombie bill; there in appearance and name but

effectively dead. And the American people still have no real protections

against the same economic dangers they faced from the financial industry in the

fall of 2008, even as many Americans seem to be unaware or, in some cases,

willfully ignorant of them.

This brings me to the next inevitable roadblock to any

attempt to bring back the most important elements of Glass-Steagall. There is,

in today’s Congress, an active ideological barrier to necessary and responsible

financial regulation. There is a school of thought among many of the

conservative members of Congress—particularly those swept in by the Tea Party

Movement of the 2010 elections—that government regulation of any kind is an

inherently bad thing. Regulation, they have stated time and again, places an

impediment on free market capitalism which, they posit, is entirely unnecessary

due to the self-correcting nature of the economic system. Of course, this

assertion is absurd. After all, many of the most fervent of free market

advocates were forced to recalibrate their ideology in the face of the economic

destruction of ‘08, including former Federal Reserve Chairman Alan Greenspan

who conceded

in a House Committee hearing that there was a “…flaw in the model that I

perceived is a critical functioning structure that defines how the world works,

so to speak”. But those

that still buy into the myth of the innate perfection of absolute free market

economics will not be dissuaded regardless of these documented concessions or

ample evidence to the contrary of their position.

One of the most important things that Dodd-Frank attempted

to do was to impose some regulation on the real monster of the financial

meltdown: financial derivatives like credit default swaps. While the housing

bubble bust was the catalyst for the crisis, it was the near implosion of nearly

$700 Trillion in outstanding, unregulated derivatives—ten

times the GDP of all the world’s countries combined—that very nearly killed

the global economy. Basically, financial institutions had made massive unofficial

side bets that they simply didn’t have the capital to cover. When the bets went

bad they set off a chain reaction of more bets going bad and as the reality of

the situation became apparent the trust so necessary to have a functioning

economy nearly disappeared overnight. Credit markets froze. People panicked.

Stock Markets tumbled. Ultimately, the government had to “inject liquidity” on

a never-before-seen scale to restore confidence. Considering this, some

oversight of the derivatives market and the amounts of capital that financial

institutions would be allowed to place in it would seem to be, once again, common

sense. Think again.

A number of bills that push for the return of deregulation of derivatives

have now made their way out onto the floor of the House of Representatives. A

co-sponsor of one of these bills, Rep. Scott Garrett, explained his support of

the bill, "Our job creators -- millions being crushed

by overly burdensome Washington

Not even five years after the world teetered on financial

ruin and potential civil unrest and many members of Congress are once again

ideologically and financially motivated to load another bullet in the chamber

for round two of Global Economic Russian Roulette. Very few stand in the way

and those that do are undeniably outgunned and outspent. It won’t be any

different for this attempt to reinstate Glass-Steagall. What McCain and Warren

(as well as Senators Angus King and Maria Cantwell) are attempting to do is

undoubtedly noble but equally impossible.